John Dee and Edward Kelley: Visual Depictions of the Renaissance Occultists at Work

(Right) Edward Kelley, unknown artist, c. 1900, Wellcome Collection, London

The stories of John Dee and Edward Kelley, notorious Renaissance occultists, are a peculiar mix of history and folklore that continue to influence artists and writers hundreds of years after their deaths. The small sample of artistic representations of Dee and Kelley below explore the lasting romantic impression they left of black magic, alchemy, and spiritualism during the English Renaissance.

For more John Dee on Curious Archive, see The Magical Relics of John Dee at the British Museum.

A (Very) Brief History of Dee and Kelley

John Dee was born in London in 1527 and attended the University of Cambridge in 1542 at the age of 15, graduating four years later with his BA. After travelling through Europe to expand his knowledge on mathematics, astronomy, and cartography, Dee was appointed astrological and scientific advisor to Elizabeth I. He specialised in navigation and advised English voyages of discovery between the 1550s and 1570s. Dee was deeply fascinated by the unknown and the idea of lost knowledge and practices that today would be considered fringe science. In 1564 he wrote Monas Hieroglyphica, a Hermetic text analysing a glyph he created to represent the unity of all creation.

Dee met occultist and medium Edward Kelley, nearly thirty years his junior, in 1582 after numerous failed partnerships with other scryers. At the time, Kelley was a known trickster, having previously been convicted of forgery. Despite this, Dee believed in Kelley’s abilities and the two dedicated themselves to seances and communication with angels. Through conversing with angels, Dee hoped to gain hidden knowledge to assist the English on their voyages of discovery and to help heal the divide between the Roman Catholic Church, the Reformed Church of England, and the Protestant movement in England.

While travelling through Europe with their families, Dee and Kelley’s working relationship began to decline. Dee’s obsession with contacting angels, which relied on Kelley’s scrying abilities, was no longer reciprocated by the younger man who was more interested in alchemical-based pursuits. The final nail in the coffin of their already tense partnership likely followed Kelley’s claim that the angels told him to swap possessions (including wives) with Dee. Dee went through with the angel’s supposed wishes, despite reluctance. Nine months later Dee’s wife gave birth to a son that may or may not have been Kelley’s, and Dee returned to England with his family. Kelley stayed abroad, eventually becoming alchemist to Emperor Rudolf II. He died in custody sometime in late 1597 or early 1598 at Hněvín Castle in Bohemia after falsely claiming he could turn metal into gold.

When Dee returned home to Mortlake, Surrey his home and extensive library had been vandalised and looted. England had become less accepting of the occult practices he had become consumed in, and after a brief time as Warden of Christ’s College in Manchester, Dee returned once more to Mortlake where he lived with his daughter Katherine and died in poverty in late 1608 or early 1609.

The following paintings and drawings explore a few curious chapters of the real and fictional histories of Dee and Kelley and the mystical and sinister reputation they left behind.

The Queen’s Conjurer

Henry Gillard Glindoni’s (1850-1913) oil painting John Dee Performing an Experiment before Elizabeth I shows the Queen enthroned atop a simple chair surrounded by elaborately dressed guests. The setting is the home of John Dee in Mortlake, Surrey, where Queen Elizabeth I visited several times throughout their working relationship.

The small gathering (which includes the Queen’s chief advisor and courtier) stares intently at Dee, dressed in black, as he pours contents from a bottle onto a small lit brazier. Edward Kelley sits behind Dee and is shown reading from a large tome. The gestures and expressions of the Queen’s companions are of wonder and curiosity. Dee’s role as ‘the Queen’s Conjurer’ is shown in a somewhat positive light as he demonstrates an unknown scientific experiment to his captivated audience.

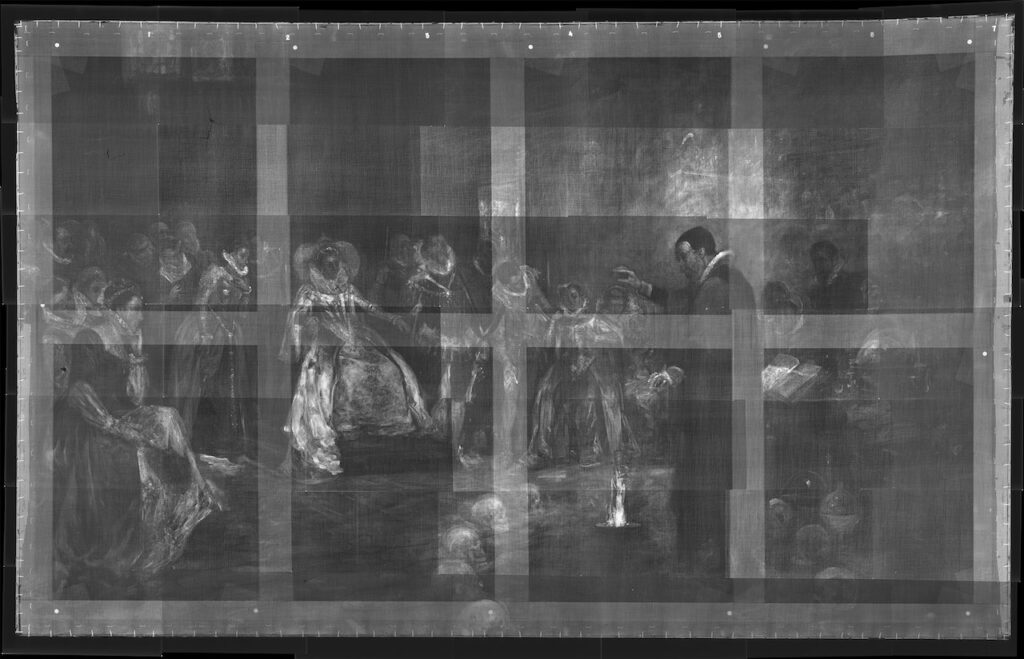

While known as an advisor to Queen Elizabeth I, Dee is arguably more famous today for his involvement with the occult. In particular, the previously mentioned rituals and experiments conducted with Kelley involving communication with angels as possible necromancy and other forms of black magic. Looking at the painting in its final form, Glindoni chose to ignore this side of Dee, and instead focused purely on his role in Queen’s court. However, after the painting was x-rayed in 2016, the artist’s original intend came to light.

Commissioned for the exhibition ‘Scholar, Courtier, Magician: The Lost Library of John Dee’, which ran in the first half of 2016 at the Royal College of Physicians in London, an x-ray of Glindoni’s painting very clearly shows the artist’s original image depicting Dee’s more notorious reputation. As seen in an image of the x-ray above, Glindoni originally included a circle of skulls surrounding Dee (and not far from the feet of the Queen), all facing the magician as he performed his experiment. Another noticeable difference in the x-ray is the absence of Kelley at the right, replaced with what looks like tools used in alchemy in his place. Analysis concluded that the skulls were painted over fairly early in the process but it’s clear that Glindoni originally intended to represent Dee not only as a scholar and court advisor, but as a necromancer and perpetrator of occult magic.

The Necromancers and the Revolutionary

Dee and Kelley were featured as fictionalised versions of themselves in William Harrison Ainsworth’s 1840 serialised novel Guy Fawkes, or The Gunpowder Treason: An Historical Romance. Guy Fawkes is an infamous figure in British history who was involved in a failed plot to blow up Parliament on 5 November 1605. The date is commemorated every year in the UK on the anniversary of the plot with fireworks and bonfires on what is known as Guy Fawkes Night or Bonfire Night. The Ainsworth novel follows Fawkes from the beginning of the plot and concludes with the execution of Fawkes and his fellow conspirators.

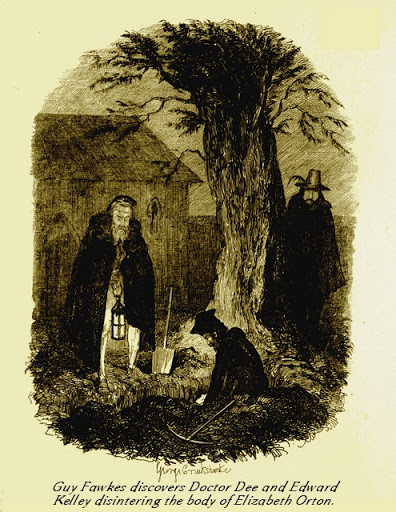

While Ainsworth’s novel covers a relatively realistic portrayal of the trial and execution, his inclusion of Dee and Kelley has more supernatural elements in line with Victorian Gothic literature. As seen through the images above, which were illustrated for the novel by British cartoonist George Cruikshank, Dee and Kelley’s main role in the narrative was focused on their occult pursuits, mainly necromancy.

In the first image, Dee stands over a grave while Kelley uses a spade to unearth the coffin-less corpse within. Hidden behind a tree, Fawkes watches the pair only to realise the corpse in question belonged to Elizabeth Orton who had prophesised Fawkes’ execution at the beginning of the novel.

In the second image, Fawkes stands before Dee and Kelley in a charnel (a building in a cemetery used to store skeletal remains) to perform a ritual to raise the corpse from the dead. To the left, a number of skeletons stand, representing a more watered down interpretation of the text which reads:

The chamber in which Guy Fawkes found himself was in perfect keeping with the horrible ceremonial about to be performed. In one corner lay a mouldering heap of skulls, bones, and other fragments of mortality; in the other a pile of broken coffins, emptied of their tenants, and reared on end. But what chiefly attracted his attention, was a ghastly collection of human limbs, blackened with pitch, girded round with iron hoops, and hung, like meat in a shambles, against the wall. There were two heads, and, though the features were scarcely distinguishable, owing to the liquid in which they had been immersed, they still retained a terrific expression of agony. Seeing his attention directed to these revolting objects, Kelley informed him they were the quarters of the two priests who had recently been put to death, which had been left there previously to being placed on the church-gates.

Book I, “The Plot,” Chapter VII, “Doctor Dee,” pp. 53-54 (via Victorian Web)

While Fawkes is appalled by the scene around him, Dee and Kelley appear unbothered. Curiously, the rest of Cruikshank’s illustration, including the magic circle on the ground and lit brazier, are not mentioned in the text. An analysis of the image on Victorian Web offers a few possibilities for the alteration including the written passage being revised after the illustration was already completed or perhaps the artist taking his interpretation of the narrative (as well as the interpretation of Dee and Kelley) into his own hands by adding more obvious supernatural elements.

The third image shows Dee and Kelley next to Fawkes who lies dying in bed after receiving a head injury in a brawl with government soldiers. The occultists had been summoned by the fictional Viviana Radcliffe (Fawkes eventual wife) who was certain Dee could revive Fawkes with an elixir, highlighting their role as alchemists.

The inclusion of Dee and Kelley in Ainsworth’s novel took a factual historical event and enhanced it with Gothic elements popular in literature during the nineteenth-century. This, along with the x-rayed version of Glindoni’s painting above, shows that even during the nineteenth-century the impression of Dee and Kelley as shady occultists continued to be an important part of their historical identity. And as with Glindoni’s painting, Kelley is often depicted as an advisor to Dee, who typically holds the main focus of the narrative. Almost like a devil sitting on Dee’s shoulder.

On Communication with Angels

A final and more recent artwork shows one of the most infamous collaborative projects pursued by Dee and Kelley – their attempts at communicating with angels through the language Enochian. Enochian was recorded by Dee and Kelley in their journals and was said to be based on the Biblical figure Enoch (writer of the Hebrew apocalyptic Book of Enoch) who Dee believed was the last human to be educated in the language. Enochian is also said to be the language spoken by Adam when he named the animals and plants in the Garden of Eden.

Sebastian Haines’ painting shows Dee (left) and Kelley (right) in the midst of the ritual surrounded by all the necessary tools: a crystal ball (or shew stone) used for scrying and communication with angels, the magical discs (also known as the ‘Seal of God’) placed at the centre of a sweetwood table decorated with Enochian inscriptions.

© Curious Archive, 2020

In Haines’ painting, two spirits are seen perched on the chairs behind Dee and Kelley. According to the Museum of Witchcraft and Magic in Boscastle, Cornwall, these spirits represent a young girl named Madimi (left) and a jester or fool spirit (right). Apparently, the jester spirit once prophesised Dee would be receiving the Book of Enoch within 28 days (though it’s uncertain if this prophecy came true). Unlike the other examples discussed, Haines’ painting of Dee and Kelley is more intimate, showing the occultists in the privacy of what is likely Dee’s library in Mortlake. Instead of Dee taking centre stage, the two sit as equals at the sweetwood table while Dee notes the conversation Kelley has with the angel in crystal ball.

Eternal Notoriety

It’s impossible to summarise the exploits and lives of John Dee and Edward Kelley, especially due to the romanticised nature of their personal histories through art, literature and other media. Whether they really were able to communicate with angels, turn metal to gold, or raise the dead is inconsequential to history who will remember them as inquisitive, if somewhat untrustworthy figures, who sought to understand a world much different than the reality we live in.

Sources and Additional Reading:

Curious Archive – The Magical Relics of John Dee at The British Museum

Dr. David Harrison – John Dee and Edward Kelley; Conversing with the Angels

Museum of Witchcraft and Magic – Reproduction Painting of John Dee and Edward Kelley

Smithsonian Magazine – A Painting of John Dee, Astrologer to Queen Elizabeth I, Contains a Hidden Ring of Skulls

The Guardian – John Dee painting originally had circle of human skulls, x-ray imaging reveals

Victorian Web – Doctor Dee in conjunction with his Seer Edward Kelley, Exhibiting His Magical Skill to Guy Fawkes

Wellcome Collection – John Dee performing an experiment before Queen Elizabeth I

Wellcome Collection – X-ray imaging of John Dee painting by Henry Gillard Glindoni

Wellcome Collection – John Dee and Edward Kelley attend to the wounded Guy Fawkes

Wikipedia – Edward Kelley

Wikipedia – Guy Fawkes (novel)

Wikipedia – Gunpowder Plot

Wikipedia – Hermeticism

Wikipedia – John Dee

Wikipedia – Monas Hieroglyphica