The History of The Brown Lady of Raynham Hall and Britain’s Most Famous Ghost Photograph

Raynham Hall in Norfolk, considered one of the most beautiful homes in the country, began construction in 1619 and was completed some fifteenth years later. The house was designed by Sir Roger, 1st Baronet Townshend, with construction lead by his Master Mason, William Edge. The hall is the first in England to be heavily influenced by European architecture, possibly a product of Roger and Edge’s travels together abroad. Unfortunately, Sir Roger died suddenly in 1637 before the completion of Raynham Hall.

by Sir Godfrey Kneller (c. 1690)

via The National Portrait Gallery

The most famous resident of Raynham Hall was Charles Townshend, 2nd Viscount Townshend (1674 – 1738). Charles’ is remembered for his role in the British Agricultural Revolution, specifically promotion of the four crop rotation method involving turnips, barley, clove, and wheat. He also advocated growing turnips as feed for livestock, giving him the nickname ‘Turnip’ Townshend. During various building restorations at Raynham Hall, Charles had architectural (as well as political) rivalry with Norfolk neighbour Robert Walpole, future Earl of Orford, as the two competed “to create the most beautiful country house in Norfolk.”

After four hundred years of occupancy, occasional stretches of vacancy, and an extensive amount of continued restorations, the estate and 7000 acres Raynham Hall continues to be the proud home of the Townshend family with the Marquesses of Townshend as the current occupants.

Today, Raynham hall is still known for its architectural splendour and dazzling interior design, but an incident that occurred almost ninety years ago has put the Hall on the map for another reason entirely.

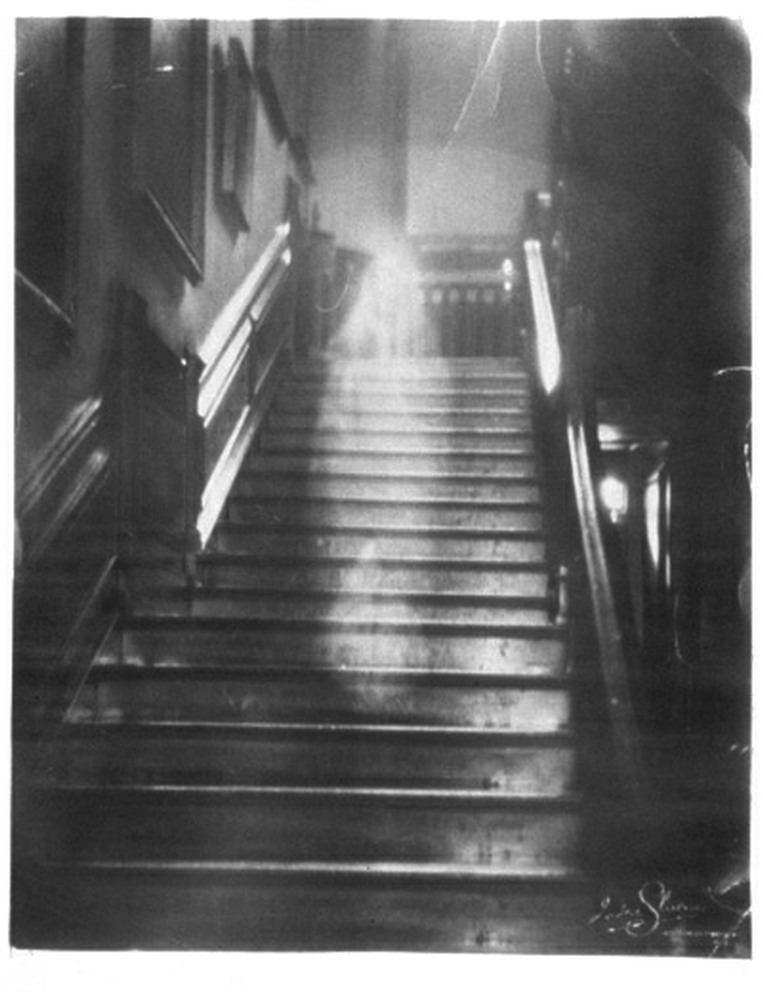

The Photograph

On 26 December 1936, Country Life magazine ran a story that would become the basis for one of Britain’s most popular ghost stories. But, more importantly, the article was accompanied by a photograph that many readers saw as proof of Raynham Hall’s haunting and the existence of life after death. The photograph was taken by Indre Shira and Captain Hubert C. Provand when the pair were at Raynham Hall taking photographs for their article. Shira then recalled the incident in Country Life when the haunting photograph was published:

… [at] about four o’clock in the afternoon, we came to the oak staircase. Captain Provand took one photograph of it while I flashed the light. He was focusing again for another exposure; I was standing by his side just behind the camera with the flashlight pistol in my hand, looking directly up the staircase. All at once I detected an ethereal, veiled form coming slowly down the stairs. Rather excitedly I called out sharply : “Quick! Quick! There’s something! Are you ready?” “Yes,” the photographer replied, and removed the cap from the lens. I pressed the trigger of the flashlight pistol. After the flash, and on closing the shutter, Captain Provand removed the focusing cloth from his head and, turning to me, said: “What’s all the excitement about?” I directed his attention to the staircase and explained that I had distinctly seen a figure there – transparent so that the steps were visible through the ethereal form, but nevertheless very definite and to me perfectly real. He laughed and said I must have imagined I had seen a ghost – for there was nothing now to be seen.

Country Life, 26 December 1936

Captain Provand brushed off Shira’s excitement and bet him £5 that the developed photos would show nothing supernatural. Which it did, or so they claim. The photo was examined by leading paranormal investigator Harry Price who determined that the photograph was indeed real and the image was published, along with Shira’s account, in the December issue of Country Life that year.

The Haunting History of the Brown Lady

When the photograph was published readers instantly connected the figure with The Brown Lady who had a history of haunting Raynham Hall. But who is the Brown Lady, and why is her spirit supposedly stuck wandering the halls of the Norfolk manor?

According to legend, The Brown Lady is the ghost of Lady Dorothy Townshend (née Walpole), sister of Britain’s generally considered First Prime Minister Sir Robert Walpole, member of the aristocratic Walpole family, and aunt of antiquarian and gothic revivalist Horace Walpole. Dorothy was born in Norfolk in 1686 and married into the Townshend family sometime before 1713 via Charles ‘Turnip’ Townshend who was widowed a couple years prior.

The details of Dorothy’s life at Raynham Hall are murky at best. And due to her connection with the Brown Lady, it’s difficult to separate fact from fiction. We know that she gave birth to at least 11 children and that she lived her married life at Raynham Hall. But the remaining details of her life are unfortunately intertwined with her ghost story and likely based on rumour and exaggeration.

According to some versions of The Brown Lady legend, Dorothy’s husband caught her in an affair with Lord Wharton (who was active in the House of Lords and working in opposition to Dorothy’s brother Robert) and locked her away in a wing of the Hall. Some say the affair occurred before her marriage, and in other stories it occurred during. Another version claims that Lady Wharton was also involved in her imprisonment.

The cause of Dorothy’s death is also a contested matter. Some stories say she died of a broken heart after being separated from her young children when she was imprisoned at Raynham Hall. Another story says her death and funeral were faked by her husband who filled her empty coffin with bricks while he kept her locked alone in a wing of Raynham Hall. However, when Dorothy died in 1726 at the age of 39, it was most likely due to smallpox and not the ‘mysterious’ death that is often attributed to her. Dorothy is buried at East Raynham in Norfolk.

By Charles Jervas, 1723–4, in the collection of Raynham Hall

The first apparent sighting of The Brown Lady was at a Christmas gathering at Raynham Hall hosted by Lord Charles Townsend (a descendent of Dorothy’s husband) in 1835. Two gentlemen, Colonel Loftus and Hawkins, who were staying at the Hall during the celebrations, claimed to see the apparition of a woman in a brown dress on the way to their bedrooms one night. Upon sketching what they saw, a number of guests claimed to have seen the same figure during their stay. A gruesome detail to Loftus’ account is that the figure had two dark pits on their face instead of eyes.

A second sighting of a slightly more violent calibre occurred sometime during the nineteenth-century by Captain Frederick Marryat (1792-1848), a novelist, pioneer of nautical fiction, and acquaintance of Charles Dickens. Florence Marryat, the Captain’s daughter, wrote an account of her father’s experience in her book There is No Death from 1891. Florence recalled the room at Raynham Hall where the Brown Lady’s portrait hung, which showed her wearing a “brown satin dress with yellow trimmings”, and described her as “a very harmless, innocent-looking young woman”.

However, the ‘innocent-looking’ woman had been causing quite the stir. Frederick was friends with Sir Charles and Lady Townshend who were living in Raynham Hall at the time, and heard complaints about guests and servants refusing to stay at the Hall after encountering the ghost. Frederick requested to stay at Raynham Hall to prove his own theory that the ‘haunting’ was actually local smugglers (as a magistrate, Frederick was aware of the increasing smuggler activity in the area) who were trying to frighten the Townshend’s out of the Hall. Frederick chose to occupy the so-called ‘haunted room’, where the portrait hung, during his stay. And since he was so convinced it was smugglers and not a ghost, he slept with a loaded revolver under his pillow.

On the third and final night of his stay, Frederick’s visit had been uneventful with no appearances of spirit or smugglers. Two of the baronet’s nephews knocked on his door after he had already changed into his nightclothes and asked for Frederick to come to their room to show him a new gun they had ordered from London. He took his revolver, laughing that it was “in case we meet the Brown Lady” and followed them into the hallway. Florence recalls what happened to her father once the three left his bedroom:

The corridor was long and dark, for the lights had been extinguished, but as they reached the middle of it, they saw the glimmer of a lamp coming towards them from the other end. “One of the ladies going to visit the nurseries,” whispered the young Townshends to my father. Now the bedroom doors in that corridor faced each other, and each room had a double door with a space between, as is the case in many old-fashioned country houses. My father (as I have said) was in a shirt and trousers only, and his native modesty made him feel uncomfortable, so he slipped within one of the outer doors (his friends following his example), in order to conceal himself until the lady should have passed by. I have heard him describe how he watched her approaching nearer and nearer, through the chink of the door, until as she was close enough for him to distinguish the colors and style of her costume, he recognised the figure as a facsimile of the portrait of “The Brown Lady.” He had his finger on the trigger of his revolver, and was about to demand it to stop and give the reason for its presence there, when the figure halted of its own accord before the door behind which he stood, and holding the lighted lamp she carried to her features, grinned in a malicious and diabolical manner at him. This act so infuriated by father, who was anything but lamb-like in disposition, that he sprang into the corridor with a bound, and discharged the revolver right in her face. The figure instantly disappeared — the figure at which for the space of several minutes three men had been looking together — and the bullet passed through the outer door of the room on the opposite side of the corridor, lodged in the panel of the inner one. My father never attempted again to interfere with “The Brown Lady of Rainham,” and I have heard she haunted the premises to this day. That she did so at that time, however, there is no shadow of doubt.

From ‘There is No Death’ by Florence Marryat (1891), p. 10-11.

A third sighting occurred in 1926 when the then Lady Townshend’s son saw The Brown Lady on the stairs while playing with a friend. The two were able to identify the woman from the portrait of Dorothy Walpole hanging on the ‘haunted room’s’ wall.

Is the Photo Proof of a Haunting?

The current Townshend family living in Raynham Hall believe that Dorothy continues to walk the corridors of the estate today. However, they don’t believe Provand and Shira’s photograph is real. When discussing the haunting Lord Charles Raynham, the son of the present Marquees Townshend of Raynham, told the BBC, “she isn’t there to haunt the house but she is still there, I know she’s there and I’m glad she’s around.” Certainly not the same reaction of fear experienced by Colonel Loftus, Hawkins, and Captain Frederick. But whether or not the current Townshend family believes their house to be haunted doesn’t apply validity to Provand and Shira’s ghostly photograph.

To add a somewhat disappointing ending to this story, the general consensus today is that Provand and Shira’s famous photograph of The Brown Lady is a fake. Looking at it through modern eyes, I’m sure we can all understand why this is the case. At the time the famous photograph was taken, The Brown Lady was likely a well known ghost story. And what better way is there to capitalise on a local legend then faking a photograph of the so-called ghost? It certainly earned Provand and Shira the attention they might have been seeking when they set out to photograph Raynham Hall for Country Life magazine.

Despite Harry Price’s affirmation that “the negative [of the photograph] is entirely innocent of any faking”, others weren’t as convinced. An investigation of the photo by London’s The Society for Psychical Research (SPR) one year later in 1937 believed the spectre was the result of the camera being shaken during a six-second exposure. Another theory is that the photographers smeared grease on the camera lens to get the spooky effect, or that the image is the result of one photograph being superimposed over another. And others have mentioned the suspicious similarities between the image of The Brown Lady and carved statues of the Virgin Mary, possibly used in the creation of the image. But however it was created, Provand and Shira’s Country Life photograph stirred an interesting conversation on the validity of ghost photography and how these convincing images were created over 50 years before modern technology.

I think we sometimes fall victim to the trap of ‘it’s old and it’s creepy, so it must be real’. But people were faking ghost photographs long before Provand and Shira, most noticeably with mediums regurgitating ectoplasm during Victorian era seances. And coincidently, the SPR also exposed a number of fraudulent ectoplasm-regurgitating mediums. So it’s safe to say that during a time when ghost stories and seances were very much still in vogue, the SPR was rightfully on the lookout for supernatural hoaxes.

Dorothy Walpole would probably find it surprising that her name lives on centuries later in the form of a ghastly spirit wandering the halls of her former home. Whether the photograph is real or a hoax, it certainly makes for an entertaining ghost story. And since the current Townshend’s don’t mind her presence, hopefully Dorothy’s spirit is haunting happily from the afterlife inside the beautiful Raynham Hall.

Sources and Additional Reading

To read more on the architectural history of Raynham Hall, please see Boyington and Draper’s fantastic essay A Concise Architectural History of Raynham Hall, Norfolk.

Additional Sources

A Concise Architectural History of Raynham Hall, Norfolk by Amy Boyington and Karey Draper (via Art & the Country House)

Art & the Country House – Raynham Hall, House Essays

BBC – The intriguing history of ghost photography

BBC – The vast history of Raynham Hall

Great British Life – 8 revealing facts about Raynham Hall

Raynham – History

House & Garden – A neo-Palladian country house reveals its treasures for the first time

A few other sources/versions of The Brown Lady ghost stories:

Countryside Books – The Brown Lady of Raynham Hall, Norfolk

Marryat, Florence. There is No Death via Google Books (full version available for free)

Mysterious Britain and Ireland- The Brown Lady of Raynham Hall

Hoaxes – The Brown Lady of Raynham Hall

Dark Tales – Brown Lady of Raynham Hall