The Magical Relics of John Dee at The British Museum

London’s British Museum is one of the most revered institutions of it’s kind in the world. Originally founded in 1753, the museum’s current collection consists of an impressive eight million objects (though the ethical ownership of some items are up for debate). Among the collection are a number of curious artefacts belonging to sixteenth-century occultist and mathematician John Dee. Housed in the historical Enlightenment Room, Dee’s Magic Mirror, Crystal Ball, and Magic Discs might not visually catch the eye of the average visitor, but despite somewhat plain exteriors their history and the life of their former owner explore an interesting perspective on the relationship between science, spirituality, and the occult during the Elizabethan period.

John Dee (1527- c.1608)

John Dee, advisor of Queen Elizabeth I and court astronomer had many academic interests including mathematics, astrology, alchemy, divination, Hermeticism, and his key role in navigation during the expansion of the ‘British Empire’ (a term he coined). A graduate and fellow of Trinity College, Cambridge, Dee was said to have one of the largest libraries in England during his lifetime which was broadly considered a center for learning by scholars all over Europe.

Though his studies are considered occult oriented fringe science today, Dee was a devout Christian and a respected, albeit controversial, figure within the scientific community during the reign of Elizabeth I. Dee believed that numbers held the secrets to the universe and he explored this through the creation of his glyph which represented unity between the sun, the moon, the elements, and fire. Queen Elizabeth I was impressed enough with Dee’s knowledge and devotion to his Christian beliefs that she bestowed upon him the revered task of selecting her coronation date. During her reign Dee acted as her astrological and scientific advisor and tutor, but his esteemed position within her court did not transfer over to her successor, King James I.

In his later life, Dee turned passionately towards his supernatural interests alongside his associate and spirit medium Edward Kelley. The two began laborious attempts at communicating with angels between 1582 and 1589 through Enochian, a language said to have been revealed to Dee and Kelley by the angels themselves. Dee’s private Journals as well as his text Liber Loagaeth (‘Book of Speech from God’) reveal written recordings of these conversations as well as extensive examples of the Enochian script. He hoped conversing with angels would provide answers to the extreme divide between the Roman Catholic Church, the Reformed Church of England, and the Protestant movement in England while achieving a global pre-apocalyptic unity.

Dee’s Magic Mirror, Magic Discs, and Crystal Ball at The British Museum

Collector’s during the Enlightenment period (1715 – 1789) were interested in both ancient and modern religious objects including amulets, charms, and other items used in ritual practice. While collectors were particularly intrigued by the ancient religions of the Greeks, Romans, Indians, and Egyptians, they were also interested in the different forms of magic and occult worship occurring at home in Britain. The following objects, once belonging to John Dee, are currently on display in The British Museum’s Enlightenment Gallery. A number of these artefacts were given to the Museum by collector Sir Robert Cotton who acquired them following Dee’s death at the beginning of the seventeenth-century.

Magic Mirror

© Curious Archive, 2020

Perhaps the strangest object on display in John Dee’s collection is his magic mirror, a somewhat sinister looking black void. The Magic Mirror, made out of obsidian (volcanic glass), originates from Mexico and was brought to Europe sometime between 1527 and 1530. The mirror was previously used by Aztec priests to conjure visions and make prophesies. Dee and Kelley would have used the mirror similarly when conversing with angels during seances performed together throughout England and Continental Europe between 1583 and 1589.

The object on the left is the mirror’s wooden case, covered in a decorative tooled leather. Following Dee’s death, the mirror and case eventually found their way into the possession of Horace Walpole, antiquarian and art historian best known for his eccentric London residence Strawberry Hill and for writing the first gothic novel, The Castle of Otranto. The inscription on the case quotes the poem Hudibras by Samuel Butler and is believed to have been inscribed by Walpole.

Crystal Ball

The object in the display case with the least available information is John Dee’s crystal ball. Made of rock crystal, the crystal ball is very small measuring only 5.2cm in diameter. This was another tool used by Dee for communicating with angels through the practice of crystallomancy or scrying (the use of a crystal ball for divination). Though there isn’t extensive information on this particular crystal ball, more has been written on a similar crystal ball belonging to Dee in the collection of London’s Science Museum.

Magical Discs

© Curious Archive, 2020

The most elaborately decorated objects from Dee’s collection are his three Magical Discs, produced sometime in the late sixteenth-century. Made from wax and engraved with detailed inscriptions and symbols, the disks would have been used in conjunction with Dee’s magic mirror for communication and decoding purposes. The larger of the three discs is referred to as the ‘Seal of God’ and, according to instructions in a manuscript written by Dee (MS Sloane 1388 at The British Library), it would have been placed in the center of a sweetwood table decorated with Enochian inscriptions. Four smaller discs, two of which are displayed with the Seal of God, would have been placed under the legs of the table. Dee’s sweetwood table no longer exists but a marble copy based on his illustrations was created a century after his death and can be seen on display at the History of Science Museum in Oxford. The marble copy is thought to have belonged to William Lilly (1602-1681), the author of popular astrological almanacs who shared Dee’s interest in angels as well as spirits and fairies.

Though its uncertain if these discs were ones Dee personally used during his seances, they appear to follow a diagram that he recorded through a conversation with the archangel Uriel on 10 March 1582.

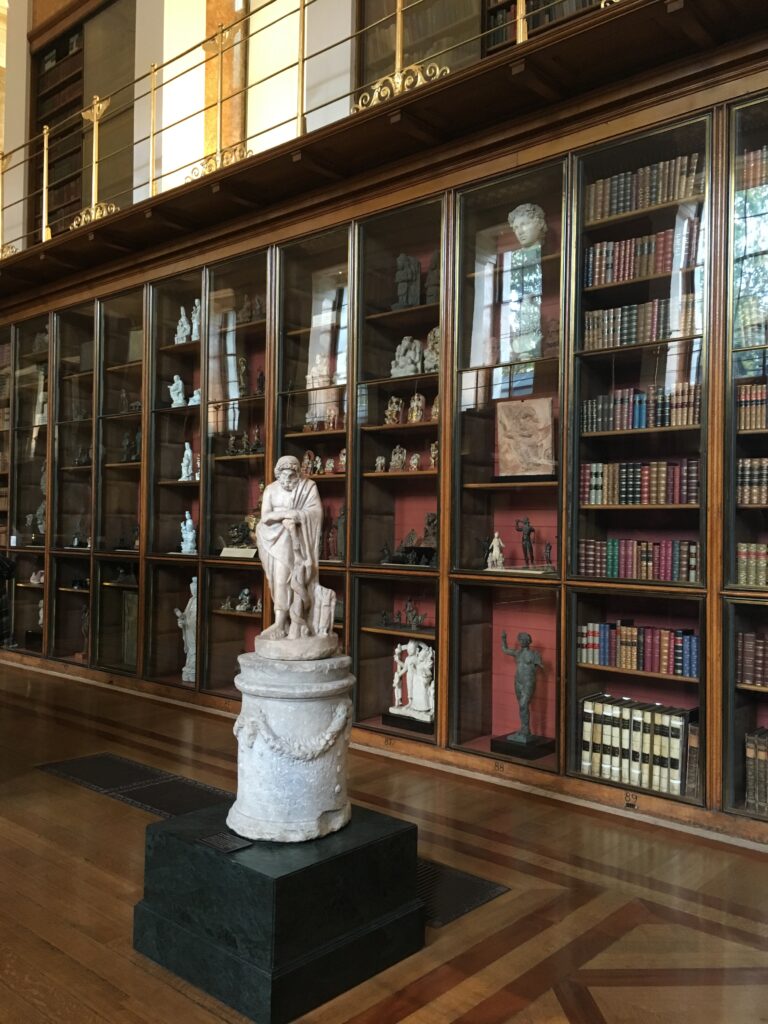

The Enlightenment Gallery

© Curious Archive, 2020

While the objects belonging to John Dee are certainly a fascinating addition to the British Museum’s collection, The Enlightenment Gallery itself is one of the most beautiful and timeless sections of the museum today.

Originally meant to house the library of King George III, the Enlightenment Gallery is the oldest remaining areas of the museum. The room and collection examines how eighteenth-century humans understood and explored the world around them through the act of collecting, cataloguing, and displaying objects.

The Enlightenment Gallery, according to The British Museum, highlights the seven major disciplines of the Enlightenment: the natural world, the birth of archaeology, art and civilisation, classifying the world, ancient scripts, ritual and religion, and trade and discovery. These disciplines can be seen at work within the large gallery’s many display cases, wall-lined bookshelves displaying ornate books and sculptures, and other interesting objects from the collections of some of history’s most fascinating individuals.

Unable to visit The British Museum in person? Take a virtual tour of the Enlightenment Gallery from the comfort of your home on their website here.

For more John Dee on Curious Archive check out:

John Dee and Edward Kelley: Visual Depictions of the Renaissance Occultists at Work

John Dee’s Conversations with Angels: Obsession and Sacrifice in the Pursuit of Heavenly Knowledge

No, John Dee Didn’t Actually Translate the Necronomicon

Sources and Additional Reading

- From the British Museum Website

– Enlightenment, British Museum

– Magical Mirror; Mirror Case

– Magical Disk

– Crystal Ball - British Library: John Dee’s Spirit Mirror

- Wikipedia: John Dee

- History of Science Museum: John Dee’s Holy Table

- Wellcome Library: John Dee’s Crystal

- The Queen’s Conjurer: The Science and Magic of John Dee by Benjamin Woolley