No, John Dee Didn’t Actually Translate the Necronomicon

That is not dead which can eternal lie,

And with strange aeons even death may die.

Abdul Alhazred, author of the Necronomicon

Polarising American author HP Lovecraft (1890-1937) wrote some deeply unsavoury things during his lifetime. But his contributions to the realm of speculative fiction are so immense that it’s impossible to ignore his continued influence on the genres of fantasy, horror, and science fiction.

Lovecraft encouraged writers to use the world and mythology he created to build off his foundation of cosmic horror, or “Weird” fiction. The Cthulhu Mythos, as it’s come to be called, includes Lovecraft’s own work as well as the work of other authors who took direct inspiration from his stories (think of it as early-twentieth century author approved fanfiction). Themes such as madness, forbidden knowledge, and the insignificance of humanity in the grand scheme of the universe (known as cosmicism) were present throughout his writing, and Lovecraft’s characters are infamous for being exposed to knowledge outside of the realm of their known reality and going ‘mad’ as a result. This is especially present in his stories involving the ‘Great Old Ones’, ancient and monstrous deities that regard humans in the same way we regard microscopic organisms.

These themes found their way into the work of popular authors such as Stephen King and Alan Moore, video game designer Kazuhiro Hamatani and manga artist Junji Ito, and is found in the art of HR Giger who was responsible for the the design of the aliens in the Alien franchise. And anyone who played World of Warcraft experienced the very obvious influence of the Cthulhu Mythos on the Old Gods lurking in the dark corners of Azeroth. It goes without saying that fans of horror, fantasy, or science fiction in any medium have been exposed to Lovecraft whether or not you’ve read his disturbing tales.

For better or worse, Lovecraft’s influence is everywhere. And the stories and lore he created were so in-depth and believable that the veil between fiction and reality, for many of his readers, became skewed. This was especially the case with Lovecraft’s most infamous creation, the Necronomicon.

The Necronomicon and John Dee

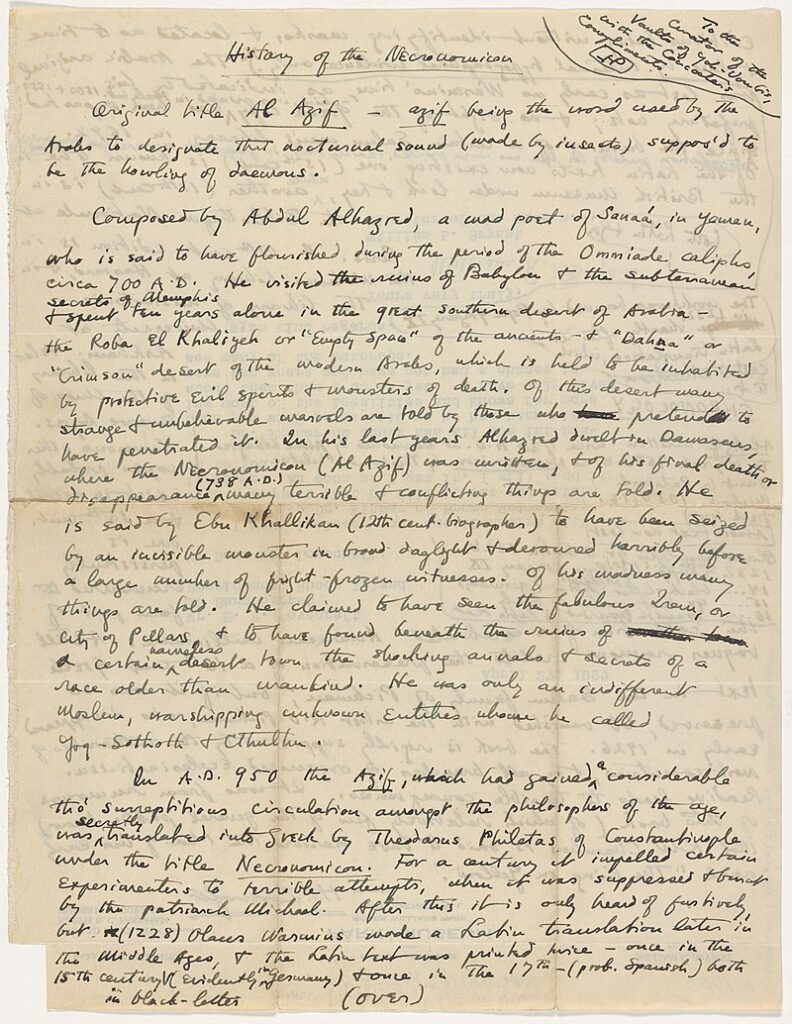

The Necronomicon (or Al-Azif) was an Arabic grimoire written by Abdul Alhazred, a loyal follower of Yog-Sothoth and Cthulhu during the early eighth-century. The book is a plot device in a number of Lovecraft’s stories and was said to contain eldritch magic and knowledge about the pantheon of old gods. Lovecraft disclosed only vague details about the Necronomicon‘s contents and general appearance, but it’s clear that whatever laid inside wasn’t meant for human consumption. None of the original Arabic or Greek copies survive, but original Latin copies were held in The British Museum, Bibliothèque nationale de France, Harvard University, the University of Buenos Aires, the Miskatonic University in Arkham, Massachusetts and a small number of private collections. Consulting the Necronomicon was thought to be incredibly dangerous and, because of this, there were numerous attempts to stop it’s circulation. It was banned by Pope Gregory IX in 1232 after it was translated into Latin, but any attempt to keep the Necronomicon from humanity’s most curious scholars was done in vain.

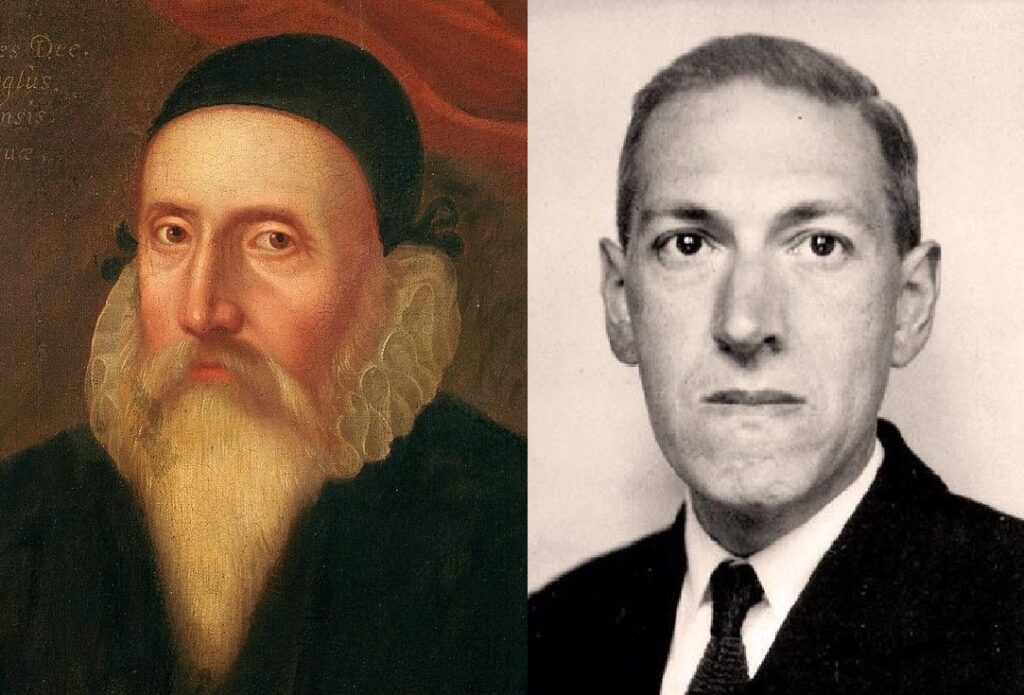

In the sixteenth-century, a Latin copy of the Necronomicon found its way into the hands of Elizabethan alchemist, astronomer, and occultist John Dee (1527-1608/9). Dee’s interest in esotericism was well documented, so a book of forbidden knowledge like the Necronomicon would have been a rare treasure for the scholar. The tome was translated into English by Dee (though the language isn’t specified, it’s assumed it was English) and was the only known copy of the Necronomicon in the language. Unfortunately, Dee’s copy didn’t stand the test of time and exists only in fragments. Dee’s translation and its poor condition is referenced twice is Lovecraft’s writing:

Wilbur had with him the priceless but imperfect copy of Dr. Dee’s English version which his grandfather had bequeathed him, and upon receiving access to the Latin copy he at once began to collate the two texts with the aim of discovering a certain passage which would have come on the 751st page of his own defective volume.

The Dunwich Horror (1929)

An English translation made by Dr. Dee was never printed, and exists only in fragments recovered from the original manuscript.

The History of the Necronomicon (1927)

These incredibly vague references to Dee’s translation make it all the more intriguing. There’s no explanation of what happened to his copy or why it’s been fragmented to such an extent. It’s possible that his Necronomicon was stolen when his library, one of the greatest of the sixteenth-century, was looted and scattered during his lengthy travels abroad. The location of Dee’s Necronomicon is currently unknown.

Is any of this real?

No, but it sounds pretty convincing, doesn’t it?

The parts about Dee including his esoteric interests (he allegedly communicated with angels through a language called Enochian) and his large, looted library are true. But that’s what makes Lovecraft’s world building so convincing. If the Necronomicon really did exist, an historical figure like John Dee is the exact type of person to try and get their hands on a copy. It makes the Necronomicon and it’s vague history all the more plausible.

So if you thought the Necronomicon (and by extension, Dee’s translation) was a real book, you aren’t alone. It’s said that enough people have been fooled by the existence of the Necronomicon that libraries and bookstores have received requests for real copies. And Lovecraft himself responded on a number of occasions to letters from friends and fans clarifying the fictional nature of his very fictional grimoire. The HP Lovecraft Archive has a list of quotes from these letters, a few of which I’ll highlight here:

- “There never was any Abdul Alhazred or Necronomicon, for I invented these names myself.” – Letter to Willis Conover (29 July 1936)

- “As for the “Necronomicon”—this month’s triple use of such allusions is bringing me in an unusual number of inquiries concerning the real nature & obtainability of Alhazred’s, Eibon’s, & von Junzt’s works. In each case I am frankly confessing the fakery involved.” – Letter to Robert Bloch (9 May 1933)

- “Regarding the Necronomicon—I must confess that this monstrous & abhorred volume is merely a figment of my own imagination! Inventing horrible books is quite a pastime among devotees of the weird…” – Letter to Miss Margaret Sylvester (13 January 1934)

Despite Lovecraft’s assurance that the Necronomicon never existed, there’s still plenty of people searching for a copy online. A quick Google search of ‘John Dee Necronomicon’ retrieves a long list of websites claiming to have legitimate PDF scans and eBay listings selling ‘real copies’. Every one of these is a work of fiction, but that’s precisely what Lovecraft encouraged writers to do. Since he never wrote it himself, the dozens of Necronomicons available online are a wonderful addition to the Cthulhu Mythos, with varying degrees of acceptance by the Lovecraft community. My only issue with some of these fan created Necronomicons is they present themselves as real first addition collectors items and insist they’re selling a real occult text that is ‘identical to the original’. It’s one thing to play in the sandbox of Lovecraft’s weird world, but it’s another thing entirely to scam people.

But why the intrigue surrounding Dee’s copy? I suspect the simplest answer is that since Dee translated the Necronomicon into English, a language accessible by more of Lovecraft’s readers than Latin or Greek. And since Dee was a fascinating historical figure with incredibly fringe interests, anything tied to the Elizabethan scholar is likely to garner curiosity. Some people naturally take it a bit further than others and refuse to separate fiction from reality, but can we really blame them? I’d also want to get my hands on copy of the Necronomicon if it was real, surely some knowledge is worth going insane for — right?

Ph’nglui mglw’nafh Cthulhu R’lyeh wgah’nagl fhtagn.

To read more about John Dee on Curious Archive, explore the John Dee tag!

Resources and Additional Reading

Den of Geek – From Lovecraft to Evil Dead: the history of the Necronomicon

How Stuff Works – How the Necronomicon Works

Royal College of Physicians – Scholar, courtier, magician: the lost library of John Dee

The HP Lovecraft Archive – The History of the Necronomicon

The HP Lovecraft Wiki – Necronomicon/Variants

The Verge – The Cult of Cthulhu: Real Prayer for a Fake Tentacle

Vox – Lovecraftian horror – and the racism at its core – explained