Émilie Sagée and the Curse of Unintentional Bilocation

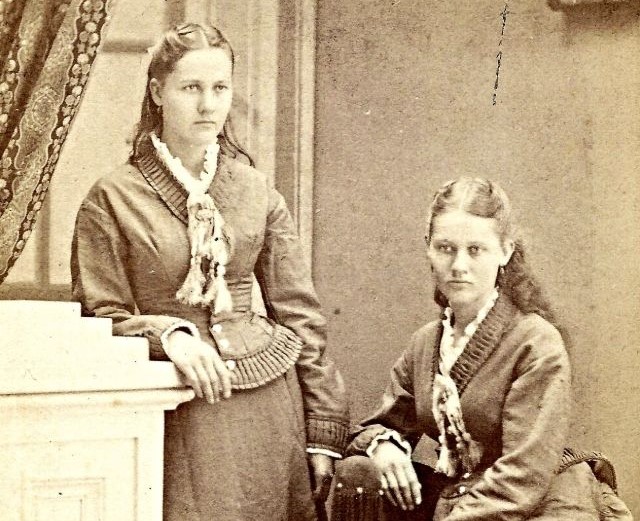

Born in Dijon, France on 3 January 1813, Mademoiselle Émilie Sagée was a thirty-two-year-old French teacher who worked at a Latvian boarding school between 1845 and 1846. She was described as blonde and blue-eyed with a mild temper and a quiet but anxious disposition. The boarding school Pensionnat of Neuwelcke had a total of forty-two students, all young girls from wealthy noble families during the time of Sagée’s tenure. At first, there was nothing out of the ordinary when it came to the school’s new teacher other than being a bit “nervously excitable”. She was considered good at her profession, was up to the high standards of the school, and liked enough by her students.

However, shortly after Sagée’s arrival at Neuwelcke peculiar rumours began to spread. Some students would claim to see her on one side of the school, while others would say they had just seen her on the other. Reports of Sagée’s location at any given time were conflicted, almost as if she was appearing in two places at once. Sagée’s colleagues told the students that they were letting their imaginations run away with them and to focus on their studies instead of filling their heads with nonsense.

Eventually, the rumours surrounding Mademoiselle Sagée became too much to ignore. A number of instances occured that drew attention to the new teacher’s strange ‘condition’, including the following:

- In front of a classroom of thirteen-students, Sagée’s exact double appeared beside her while she was writing lesson notes on the chalkboard. The double mirrored her movements exactly, but did so without chalk in its hand. Each of the students in the class agreed that they had witnessed the same phenomenon.

- Sagée was helping a student fasten the back of her dress while standing in front of a mirror. The student looked into the mirror and suddenly realised there were two Sagée’s reflecting back at her, both making the same motions of fastening her dress. The student was so shocked that she fainted.

- Occasionally Sagée’s double would stand behind her chair while the school had their dinner and mime Sagée’s exact motions of eating. Other times Sagée would stand from her chair and her double would remain seated.

- When Sagée was sick with influenza a student was reading to her from her bedside to help keep her spirits up. The student recalled her teacher suddenly becoming stiff, pale, and dazed. Worried, the student inquired if she was feeling worse but Sagée declined. However when the student looked to the side she realised the other Sagée was pacing up and down the room they were in. The real Sagée did not seem to notice.

The most notable incident occured in front of all forty-two students at Neuwelcke. On this day the students were in one room together sitting at a long table to practice their embroidery. Through large glass doors they were able to see Sagée outdoors in the garden picking flowers. The teacher who was leading the lesson would occasionally get up and exit the room, leaving her seat at the front of the class vacant. However, shortly after the other teacher would leave, Sagée would appear in the chair. The students observed that while Sagée sat before them, they could also see her continuing to pick flowers in the garden through the windows. The only difference was the Sagée out in the garden was moving much slower, as if she were very tired.

Two of the girls were brave enough to approach the ‘other’ Sagée at the head of the table. They touched the figure and described it feeling like “a fabric of fine muslin”. One of the girls allegedly passed partially through the other Sagée. The figure eventually disappeared and the real Sagée in the garden seemed to snap out of her daze and continue picking flowers. When the students questioned Sagée about the incident afterwards, she told them that she had noticed the chair vacant and thought to herself that she wished their embroidery teacher hadn’t left because she was sure the girls would get up to trouble unsupervised. However, Sagée did not recall anything else about the incident other than her own experience in the garden.

The peculiar apparitions appeared frequently and at random for the short time Sagée taught at Neuwelcke. Her double would appear more often indoors, but would occasionally appear during walks outdoors as well. The other Sagée was never far from her and never appeared somewhere without the real Sagée nearby. The fact that she was not aware that anything peculiar was happening, nor did she ever actually see her other self, made the situation even more bizarre.

It wasn’t long before parents caught wind of the unexplained situation at Neuwelcke. Some of the students found the apparitions upsetting and their parents began to worry about leaving them in the care of the school, and especially in the care of Sagée. A number of students failed to return to the school after the holidays, but the directors were determined to keep Sagée employed as they felt she was an wonderful teacher and didn’t deserve to be fired over something out of her control. However, the attendance of the school eventually fell from forty-two to twelve after eighteen months of Sagée’s employment, so the directors had no choice but to let her go. When this occurred, she was incredibly upset and disclosed that this was her nineteenth-time being dismissed from a teaching position. She had previous been employed at eighteen different schools that had praised her teaching abilities, but parted ways for undisclosed reasons.

Sagée left Neuwelcke and moved in with her sister-in-law and her young children. Her double followed and continued to appear at random, as witnessed by her nieces and nephews who would exclaim that there were two Aunt Émilies. She then moved to Russia and was never heard of again.

The Source of the Strange Case of Émilie Sagée

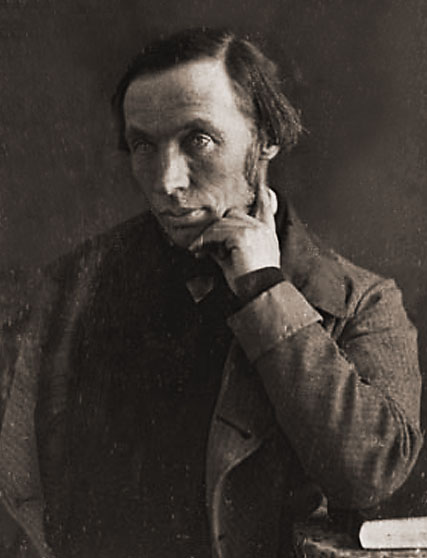

The above tale is a summary from Robert Dale Owen’s book Footfalls on the Boundary of Another World (1860) and was told to the author by Mademoiselle Julie de Guldenstubbé, a former student at Neuwelcke when Sagée worked there. Author Robert Owen (1801-1877) was an American politician and social reformer who was incredibly outspoken against slavery and supportive of women’s rights (so we love him). He also had a keen interest in spiritualism and the supernatural. Footfalls, along with the curious story of Mademoiselle Émilie Sagée, contains other accounts of strange and unexplainable occurrences including dreams, ghosts, living and dead apparitions, and hauntings. His book documents things Owen had witnessed first-hand as well as supernatural events that had been published in academic areas including psychology.

But who exactly was his source Julie de Guldenstubbé? As the single recorded witness of the event, can we put much faith in her testimony? According to Owen, Julie was the daughter of Baron de Guldenstubbé and some digging through online sources confirms that her brother Ludwig von Guldenstubbé was involved in the early promotion of seances in France. He was best known for experiment with direct writing, leaving blank paper and writing materials in places like churches, galleries (such as the Louvre), tombs, and on statue pedestals. He claimed that when he would return to retrieve the paper he would find writing in various languages from people throughout history including Plato. Eventually he stopped leaving a pen and would still discover the paper covered with writing — even when he had allegedly locked the blank paper inside a box. It’s said that a number of people witnessed the phenomenon first-hand and his experiments were celebrated by English Spiritualists. Interestingly, Julie was just as involved with the spiritual community as her brother and worked as a medium while editing her brother’s scientific publications.

I’m unsure the date Owen and Julie spoke about her experience at Neuwelcke, but it was presumably during the time Julie was already involved with the paranormal community. Does this make her an unreliable source? It certainly raises questions of the legitimacy of her claims, perhaps likening her more to a good storyteller. Or could her experience with spiritualism have given her the ability to properly describe the strange experience she had as a child? We also need to rely on Julie’s narrative for the reactions of the other students and teachers at Neuwelcke. To put it plainly, we only know that everyone else at the school witnessed Sagée’s double because of Julie’s testimony.

A later source of the story comes from the 1921 book Death and Its Mystery. Author Camille Flammarion, a French astronomer and psychical researcher, rehashes the original account by Owen while including the name of the headmaster of Neuwelcke at the time of the incident, a Monsieur Buch. Flammarion claims to have known Julie and her brother (presumably how he learned the name of the headmaster) in 1862 and described them as being “most sincere, perhaps a little mystical, but of unexceptionable integrity” (p. 42). As with Owen’s account, we’re fully relying on someone who spoke personally with Julie but came away without any real evidence to validate her claim.

Locating Pensionnat of Neuwelcke

From our sources, what do we actually know about the mysterious Pensionnat of Neuwelcke? The French word ‘pensionnat’ translates to ‘boarding school’ in English, so the name literally means the Boarding School of Neuwelcke. Owen describes the school as being “in Livonia, about thirty-six miles from Riga and a mile and a half from the small town of Wolmar” (p. 346). At the time of writing Footfalls, Owen states that the school still existed and had recovered from the soured reputation it garnered during Sagée’s time teaching. But no school under that name seems to exist today, nor is there any information readily available about the school during the time Sagée taught there. Or at all really… it almost seems like the school never existed.

But we can find references to Neuwelcke – it appears that the area is known today as Jaunveļķi. Searching for Jaunveļķi on Google turns up a result for a boarding school at this location. Putting the coordinates from that website into Google Maps and using Street View shows a farmhouse and some outbuildings, but they’re mostly obscured by shrubs and trees. The website above does include photos of this location, but it doesn’t look like the current building(s) are large enough to house forty young girls and staff. There is an oil painting by an unnamed artist that claims to be the school during the nineteenth-century but I can’t find where this painting came from and searching for it online using Google image search only links back to this same website.

Since there is little else linking this particular property to a former girls boarding school I’m not entirely convinced that this was the location of the story. Searching for Jaunveļķi (or Jaunveļķu) on Google Maps returns a cave named ‘Patkula ala’ for some reason, so I think there might be a language barrier that limits our the hunt for Pensionnat of Neuwelcke. Either that or the school never existed at all, I can’t confidently say either way.

Did Émilie Sagée Actually Exist?

As with the rest of the story, the existence of our cursed protagonist Émilie Sagée relies entirely on Julie’s account. While Owen is confident enough with her original testimony, Flammarion does some additional digging when staying near Dijon (Sagée’s hometown) in August of 1895. His findings are quoted below:

The civic records of Dijon contain no family named Sagée; but they record the birth, on January 3, 1813, of a child named Octavie Saget–as a “natural daughter.” This name is so like that of the teacher that it is difficult to doubt the identity. Would not her wandering life in Germany and in Russia be partially explained by her irregular birth? Could Mademoiselle de Guldenstubbé’s memory have confused the given name,–a mistake slight enough, moreover,–as well as the spelling of the name? That is possible, in view of the fact that all these statements were made in foreign languages. Could the teacher, alarmed by her eighteen changes of position, have herself made a slight change in her name?

Death and its Mystery at the Moment of Death by Camille Flammarion, p. 43.

I’ve bolded Flammarion’s point about statements being made in foreign languages (aka not originally in English) because I think it’s generally wise to consider errors and changes that will naturally occur during translation. An obvious example of this is with The Bible, but it can be applied to any research done where the source material was written in a language other than the one it’s being presented in. Even Flammarion’s book has been translated into English. Whether or not the name of Mademoiselle Sagée suffers from this same issue isn’t possible to say. Flammarion references an additional work by Charles du Prel titled La mort et l’au-delà (1905) that refers to Émilie as Émilie Saget, which lines up more with the Octavie Saget he uncovered in Dijon. Perhaps du Prel is using the ‘proper’ spelling of the name that was misspelled in the initial account. It’s all guesswork at this point.

Flammarion’s conclusion that Octavie Saget being born out of wedlock explains why there is no record of that family name in Dijon certainly makes sense. As does his question of whether or not Julie remembered the name of her former school teacher incorrectly. And I agree that it’s likely if anyone (whether its in the 1840s or the 2020s) experienced being fired from a position within their field nineteen times because of an uncontrollable and unexplained supernatural occurrence… a name change wouldn’t be completely off the table. But none of this is proof that Octavie Saget was actually Émilie Sagée or whether or not Émilie Sagée existed in the first place. It’s a bit sad if she did because other than Julie’s account of her, she simply vanished from history. But the fact that only Julie has mentioned Sagée, when she was fired nearly two dozen times for the same incredibly unsettling reason, is suspicious. If this was all true there were possibly hundreds of witnesses to Sagée’s double, so why did only Julie come forward?

Of Doppelgängers and Bilocation

Let’s assume Julie’s story is true and Émilie Sagée really was able to unwillingly produce a second self — what’s the paranormal explanation for this type of phenomenon? A popular theory is that Sagée was being ‘haunted’ by her doppelgänger. German for ‘double walker’, there are a number of superstitions surrounding the exact double of another person, and most of them involve bad luck or impending death. The (excellent and highly recommended) film Us (2019) directed by Jordan Peele and staring Lupita Nyong’o explores this frightening and nefarious side of being hunted by your own doppelgänger. Peele drew inspiration for his film from a Twilight Zone episode titled Mirror Image (1960) where a woman is being stalked by her “evil double from a parallel world” that’s trying to kill and replace her. This concept has been echoed on internet forums and in urban legends for as long as we’ve been using the word as paranormal terminology. We kind of love doppelgängers, even if we’re scared of them.

But is this really the best explanation for Émilie Sagée’s condition? The whole narrative around doppelgängers feeds into the fear of bumping into our own ‘other self’, but Sagée was only aware of her double’s existence because she was told. As far as we know, she never saw her ‘other’ with her own eyes. What she was experiencing could certainly be considered bad luck since it essentially ruined her career. But unlike the typical paranormal doppelgänger, Sagée’s double sounded more linked with her – almost as if a piece of hers soul was peeling away. Which brings us to our second theory: could Sagée have been experiencing ‘bilocation’?

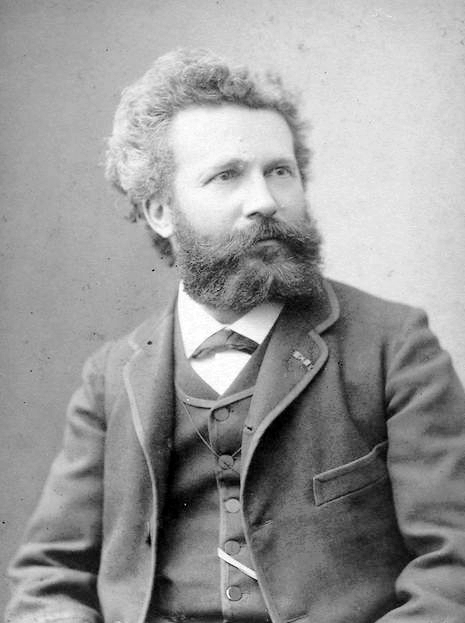

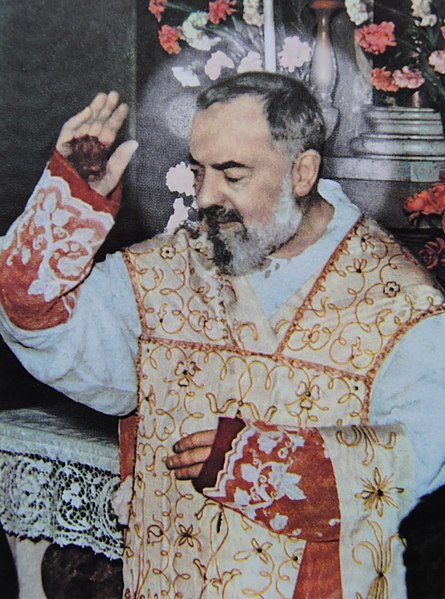

Bilocation is the ability for a person to appear in two places at the same time and has a strong basis in Christian history with numerous priests, nuns, and saints claiming to have been able to accomplish the feat. A modern day example of bilocation comes from Saint Pio of Pietrelcina (1887 – 1968), an Italian Franciscan Capuchin friar and priest. Saint Pio was associated with a number of miracles that included being marked with stigmata in 1918 and restoring sight to a young girl born without pupils in 1947.

But for our purposes, we’re interested in Saint Pio’s alleged ability to be in two places at once. It was said that he was seen all over the world at various times by a wide range of witnesses despite him almost never leaving the convent of San Giovanni Rotondo in Italy during his lifetime. In 1921 he was questioned under oath by Bishop Rossi and Saint Pio told him that:

It did happen to me in the presence of this or that person, in this place or that place. I do not know if my mind was transported there, or what I saw was some sort of representation of the place or person. I do not know if I was there with my body, or without it. […] One night I found myself at the bedside of a sick woman, Maria Massa, in San Giovanni Rotondo. I was in the convent. I think I was praying. I didn’t know her personally. She had been recommended to me.

From a conversation between Saint Pio and Bishop Rossi in 1921 (source)

It’s thought that bilocation is a gift from God to help His most impassioned devotees perform acts of charity in multiple locations at once. Like Sagée, Saint Pio was uncertain how his ability worked, but he was aware when it was happening. Though Sagée felt faint when a particular strong bilocation occurred, Saint Pio said that when someone experiences bilocation “they cannot know if the body or the soul moves, but they are very conscious of what happens and they know where they are going” (source).

We don’t know how conscious Sagée was of her situation since we only have Julie’s version of the story. We also don’t know if she could see through the eyes of her double or if her double was ever seen speaking to anyone. Her double was more like a weird shadow more than anything. Sagée was teaching at a religious school, but her devotion to her beliefs isn’t known so we can’t really categorise Julie’s story in a religious context.

It’s interesting how Sagée’s alleged experience doesn’t seem to fit neatly into a box and seems to borrow aspects of other psychical conditions. If she was real, her life sounded terribly tragic and lonely, which is heart-breaking considering the kind way Julie described her. And if Julie made the whole thing up then she has an incredible imagination and it’s a shame she never turned the story of Émilie Sagée into a novel. While Owen’s original record of Julie’s story sounds convincing, the strange tale of a teacher that appeared in two places at once is another example of why it’s important to question everything you read when delving into high strange topics. Much like the Meowing French Nuns, the closer we look at these types of paranormal tales, the more their legitimacy begins to crumble.

Sources and Additional Reading

Estofennia – Siihen aikaan kun Saarenmaan meedioparonittaren haamut ja kaksoisolennot Pariisia värisyttivät (2020)

Flammarion, Camille. Death and its Mystery at the Moment of Death: Manifestations and Apparitions of the Dying: “Doubles,” Phenomena of Occultists. New York: The Century Co. 1921.

Miracles of the Saints – Bilocation of St Padre Pio

Owen, Robert Dale. Footfalls on the Boundary of Another World. Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott & Co., 1860, p. 348-359.

Wikipedia – Bilocation / Doppelgänger