HMS Eurydice: The Ghostly Ship that Haunts the Isle of Wight

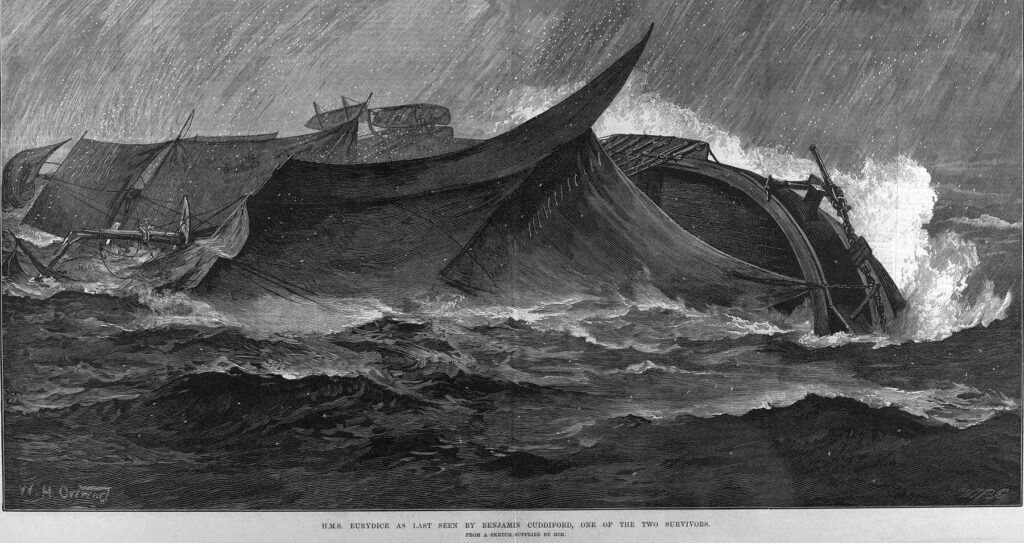

In 1878, three-year-old Winston Churchill watched alongside his nurse as the HMS Eurydice sank off the coast of England’s Isle of Wight. The tragedy, which took the lives of over 300 men, would become one of the most devastating peacetime naval disasters in British history. According to legend, the phantom ship continues to sail off the coast of Sandown and Shanklin over 100 years after her fatal voyage.

[The Wreck of the “Eurydice” by Henry Robins. Oil on canvas, 1878. In the Royal Collection (source).]

Built in Portsmouth during the 1840s, the 26-gun Royal Navy corvette was converted into a seagoing training ship in 1877. Following a three-month journey through the West Indies captained by Marcus Hare, Eurydice was on her way back to Portsmouth from Bermuda when she was caught in a freak snowstorm off the coast of the Isle of Wight. The storm hit as the ship arrived in Sandown Bay and, according to eyewitnesses, disappeared into the squall with her gun ports open — a curious detail since they should have been closed at the time. Failing to navigate through the storm’s zero visibility, the Eurydice was blown onto her starboard side and began to sink when water flooded through the open gun ports.

As the Eurydice sank, the majority of the crew were trapped inside and those who attempted to swim to shore were sucked down with the ship. According to reports two other vessels were out on the water when the storm hit, a fishing boat and the schooner Emma. Both the schooner and fishing boat reacted appropriately to the approaching storm, but the Eurydice had pressed on despite the impossible sailing conditions. No one knows why Captain Hare chose to sail into the storm, but it’s clear the faith he placed in his ship’s ability to survive was tragically misplaced.

[HMS ‘Eurydice’ at sea by William Howard Yorke. 1871. In the collection of Royal Museums Greenwich (source).]

After the storm passed, Emma sailed to the wreckage to rescue survivors, though she was only able to save five from the freezing waters. Only two of these men survived, Sydney Fletcher of Plymouth and Benjamin Cuddiford of Bristol. The Times reported that Cuddiford, who was a strong swimmer, heard cries of help from his fellow sailors as they drowned around him. He attempted to save two of his shipmates but ended up with four clinging onto him, forcing him to push them all off or risk drowning himself. Both Cuddiford and Fletcher were treated by a Dr Williamson at Bonchurch’s Cottage Hospital and presumably made a full recovery.

On 26 March 1878, Charles Beresford, Commander of the Royal Navy, wrote to the Editor of The Times about his concerns over the use of seagoing training ships going forward:

The Eurydice had a rare good seaman for a captain, and her officers were picked for being well qualified to fill the position they were appointed to – that of training youngsters in the duties which develop seamen. It is, also, a most unfortunate calamity as regards the service, as it was the first ship that was used as a training sea-going ship to bring up our young hands for the Navy, and the sad loss of her and her fine young crew may prejudice the mind of the country against the most necessary system for teaching and training our men as seamen for the fleet.

Charles Beresford to the Editor of The Times, 26 March 1878

Coincidentally, the ship that replaced the HMS Eurydice, the HMS Atalanta (renamed from HMS Juno), would meet a tragic end when she disappeared at sea along with her crew two years later in 1880. It’s believed that Atalanta was also confronted by a deadly storm somewhere in the Atlantic between 12-16 February after departing from the Royal Naval Dockyard in Bermuda. The loss of the Atalanta was criticised for it’s lack of experienced sailors (only 11 able seamen on board among 300 young trainees), while others have attributed the disappearance to the fabled Bermuda Triangle.

The Return of the HMS Eurydice?

Ghost stories often emerge from the ashes of tragedy, and the loss of the HMS Eurydice is no exception. Since her sinking, eyewitnesses have allegedly spotted the Royal Navy corvette sailing in the waters along the coast of Shanklin and Sandown near Dunnose. It’s said that the ghostly ship vanishes before it can be approached, disappearing eerily into the mist of the English Channel. While most sightings are attributed to superstition and tricks of the light, two sightings of the ghost ship in particular have raised the eyebrows of naysayers over the years.

In the 1930s, Commander F. Lipscomb of a Royal Navy submarine allegedly witnessed the HMS Eurydice appear in front of his vessel off the coast of the island. Panicked, Lipscomb managed to evade the ship only for it to disappear into thin air. A second notable sighting took place on 17 October 1998 when Prince Edward, the youngest child of Queen Elizabeth II, claimed to see the ghost ship while filming Crown and Country on the Isle of Wight. His film crew also claimed to see the Eurydice and allegedly captured footage of the phantom vessel on tape. However, the location of this footage is unknown… if it exists at all.

Remembering the Lives Lost

With so many casualties, it took some time for the bodies of Eurydice‘s crew to be found. Some were located when the ship was eventually recovered, while others began to wash up on shore along the east coast of the island. The latter were buried in either Shanklin Cemetery and Christ Church in Sandown, depending on where they were found. Four additional bodies, two identified as David Bennett and Alfred Barns, are buried in Rottingdean St Margaret’s churchyard. The bodies recovered during the salvaging of the ship were buried at Haslar Royal Naval Cemetery in Gosport. It’s unclear if the bodies of all the deceased sailors were discovered and if every corpse was properly identified. Considering the number of months some of the bodies would have spent underwater, it’s likely more than a few were buried without a name.

A number of memorials for the Eurydice were erected on and off the Isle of Wight including one in Shanklin Cemetery, another at Christchurch in Sandown, and one at Haslar Cemetery in Gosport on the mainland. A memorial at St Anne’s Church in Portsmouth lists the names of the Eurydice‘s crew, a sombre reminder of the sheer number of young lives lost that day.

So if you’re on the Isle of Wight and you’re among the lucky few who spot the phantom ship on the horizon, spare a thought for the Eurydice‘s young, ghostly crew who met their end on one of the darkest days of British naval history.

Sources and Additional Reading

BBC News – Haunted history of HMS Eurydice (2009)

Imperial War Museum – Memorial: HMS Eurydice

The Illustrated London News – Clippings about the HMS Eurydice from 1878

The Portsmouth News – NOSTALGIA: Ghostly sightings of Portsmouth frigate lost in snowstorm 140 years ago (2018)

Wightpedia – Eurydice (HMS), shipwreck

Wikipedia – HMS Eurydice (1843) / HMS Juno (1844)